An October 1900 review of the Exposition Universelle,

focused on art and architecture, casts a critical eye over the fair that

contradicts the praise and enthusiasm of many other guests. Shelton, an

American observer, has no kind words for the architectural environment of the

fair, despite the focus on decorative unity in the exhibition program. He

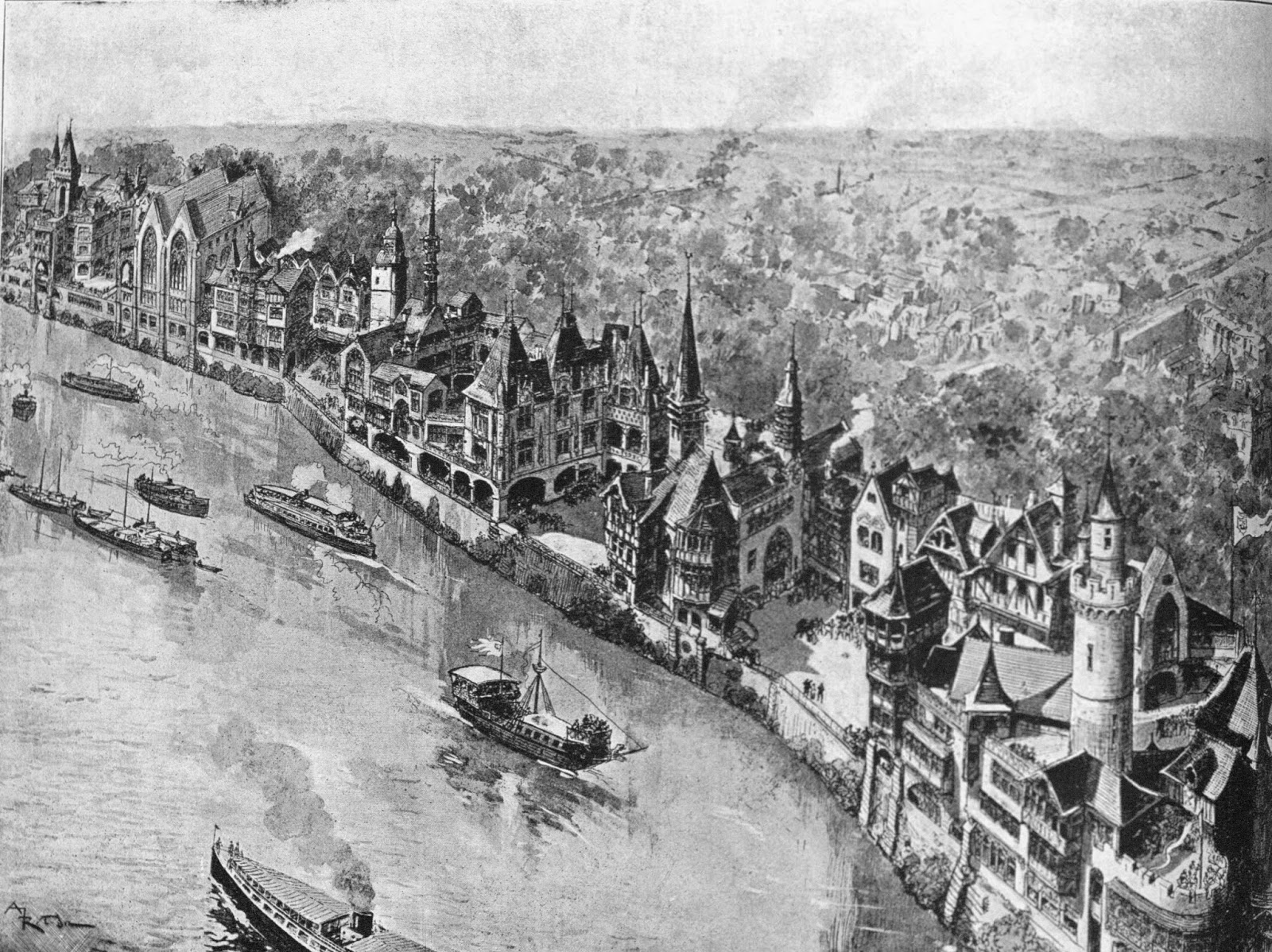

refers to the plan, divided by the Seine, as being in a “broken condition”

whose only boon was to emphasize the unique appearance of wildly diverging

styles of architecture. Struggling to find permanent structures for comment,

Shelton dismisses the fair architecture as a “potpourri of heterogeneous

ingredients” in “rococo… stucco… piecework.”

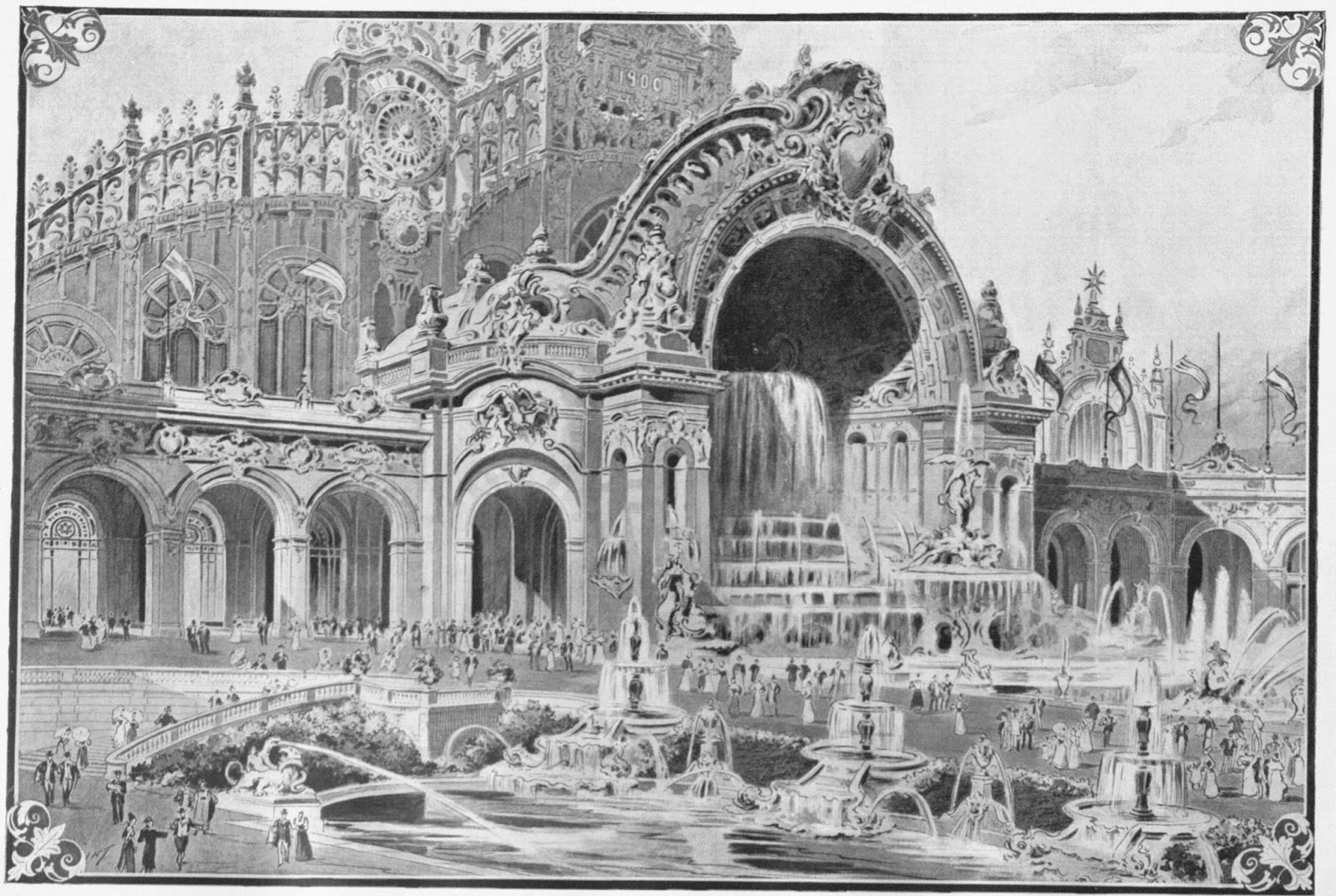

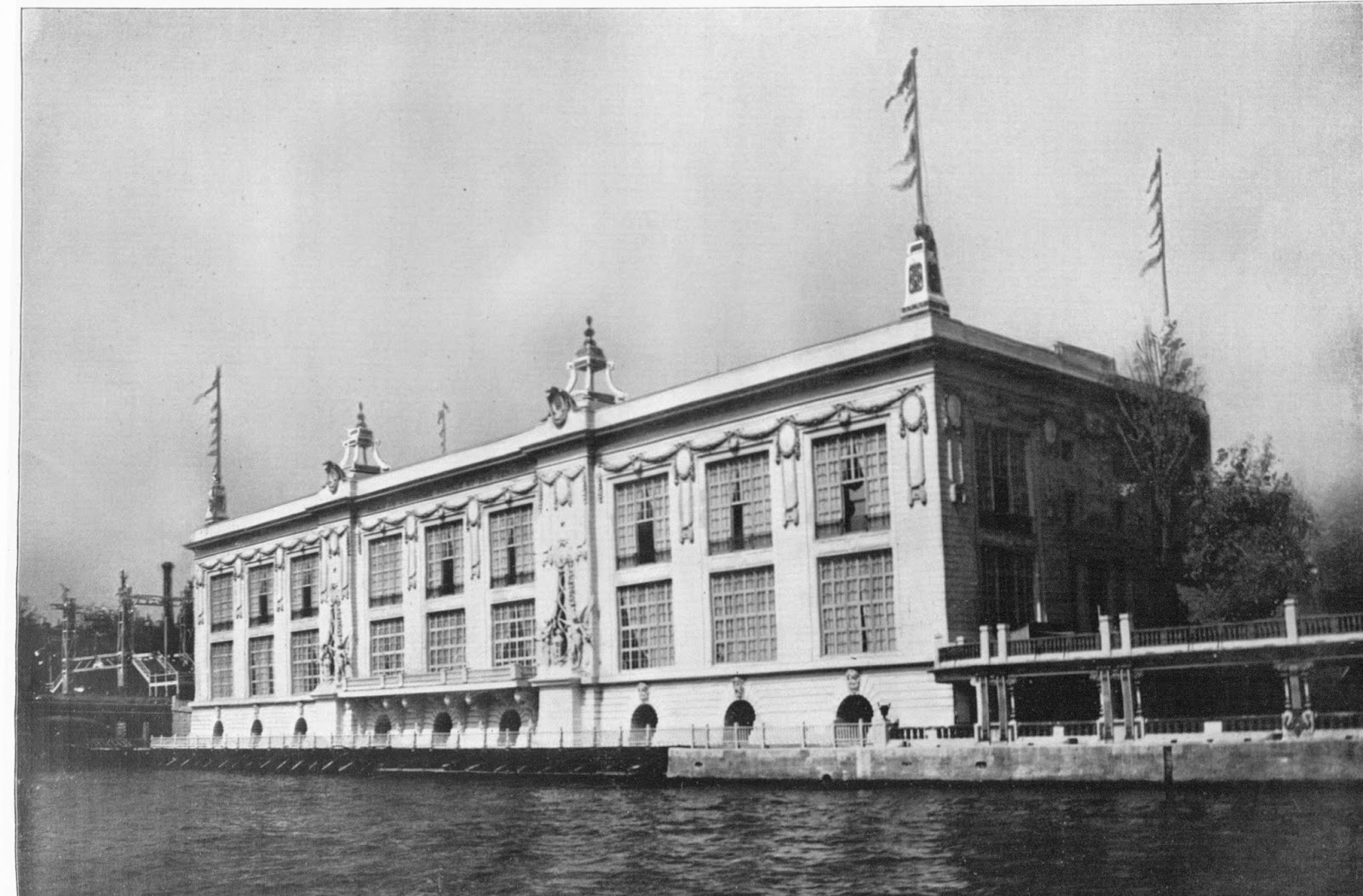

He reserves his strongest praise for the Petit Palais, the smaller of the

two Beaux-arts palaces and permanent, and admires the Danish building for its

“national characteristic.” The United States pavilion, however, he dismisses as

a travesty, as “a box to support a dome to support an eagle” that cannot

qualify as architecture. (222) He expresses this distaste elsewhere in his

article, reporting a “chorus of disapproval” for the building which resembled

little more than a post-office. (220) Instead, he claims, the United States

should have shown Washington’s house at Mount Vernon as a nationally

characteristic colonial style and filled it with old Colonial furniture.

Despite this adamantly worded passage, Shelton seems to miss the irony of

depicting the rising young American nation through the architecture produced

during its subordination to British rule.

|

| The offending U.S. pavilion, indeed with an eagle on top. |

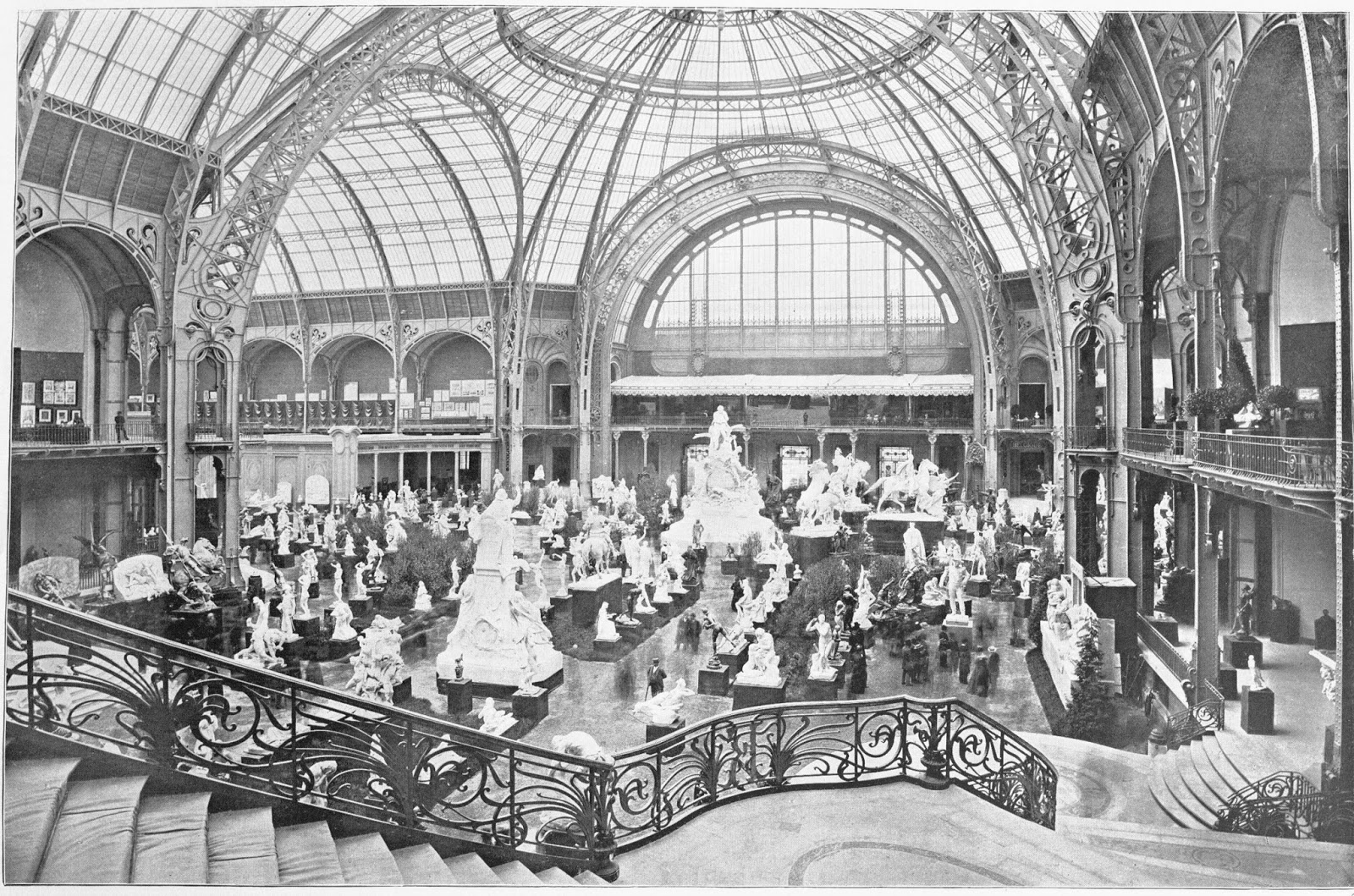

Shelton’s review is largely typical in its

discussion of art displays at the exposition. One nation’s art has devolved,

another’s has advanced; France, for example, has lost its soul and dedication

to “art for art’s sake,” shifting in tone between “mannerism and affectation,” “academic

emptiness,” and “morbid realism.” The German exhibition has shown the most

improvement since 1889, and Shelton imagines that secessionists have helped

bring about the “departure from academic tenets” and “Dusseldorf reminiscences.”

(226) The author makes a characteristic dismissal of Japanese painting and its “transition…

from old Japanese art to pure European,” and mistakes the modern school of

nihonga painting for that of “old Japan” contrasting with their oil works.

This whole review of the fine art of various nations does

conflate the country directly with their representation at the exposition, and

the act of visiting with patriotism- an American’s visit to see the country’s

art referred to as “natural and patriotic.” (225) However, the author’s discontent

with this arrangement suggests a transformation of concepts of natural identity

in art. Despite increasingly itinerant artists such as Thaulow, Carlos Schwabe,

Kaemmerer, and so forth, artists are always lumped in with the country of their

birth. This is also inconsistently observed, which Shelton claims pollutes the

United States display with newcomers and a frustrating among of

characteristically weak inconsistent and weak painting practiced by Americans

abroad in Paris. Meanwhile, some artists such as Whistler are cosmopolitan enough

to belong in an international division. (222)

Although an insistence on the conflation of nation and style

pervades Shelton’s review, this latter paragraph reveals the many weaknesses of

this system based on national division. Not only does it radically disadvantage

an innovative younger generation by expectation of an older era, as in the case

of Japanese painting and American architecture, but it quickly loses any meaning when artists travel abroad,

sometimes permanently, in increasing numbers. The impression that a handful of

Americans working abroad was enough to disrupt the impression of a “truly

American school,” and that several artists had passed into an “international”

idiom, may serve as evidence that painting was gradually breaking away from

conflicts of national character and contests of national academies.

.png)

.png)